Background

Twitter has become an important communication channel in times of emergency.

The ubiquitousness of smartphones enables people to announce an emergency they’re observing in real-time. Because of this, more agencies are interested in programatically monitoring Twitter (i.e. disaster relief organizations and news agencies).

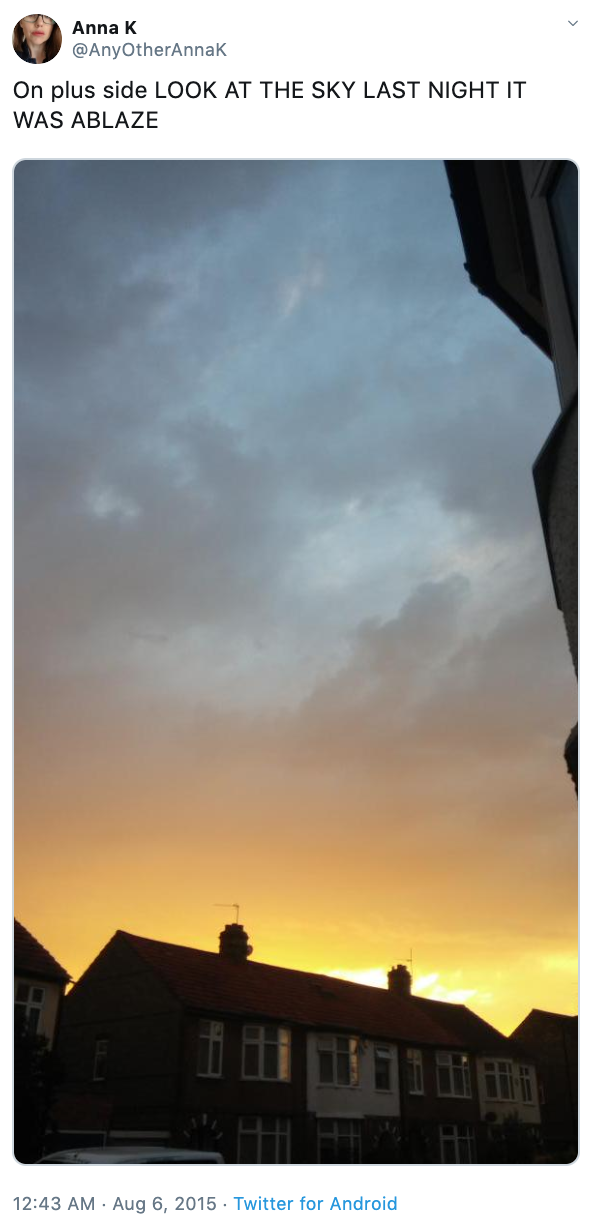

But, it’s not always clear whether a person’s words are actually announcing a disaster. Take this example:

The author explicitly uses the word “ABLAZE” but means it metaphorically. This is clear to a human right away, especially with the visual aid. But it’s less clear to a machine.

In this competition, we’re challenged to build a machine learning model that predicts which Tweets are about real disasters and which one’s aren’t.

Introduction

In Part 1 of this project, I covered 1) the architecture of Transformer model, 2) solving this problem using pre-trained Transformer LM, 3) the result and some analysis of the result. After I was done using the pre-trained model, I was curious if homemade model would behave better, so I started from the ground up by building the encoder architecture, train it, and fine-tuning using various different combinations of hypter-parameters. I also added text-preprocessing. It turns out the model can render to be 2.5-3% higher than using pre-trained model using a much smaller model, a 5-fold Stratified Cross Validation, and saving models at each epoch if it’s the best model seen so far depending on validation accuracy.

The Algorithm

First the data is preprocessed by transforming each words to lowercase, strippping stopwords, html, numbers, punctuations, etc. Then, each word is lemmatized using WordNetLemmatizer from the package nltk. Moreover, I limited the tweets to only containing the top 17k most common words, set max length of tweets to 16 words, transformed words to ids:

vocab_size = 17000 # Only consider the top 17k words

maxlen = 16 # Only consider the first 16 words of each tweet

train_data = train_data.fillna('')

train_data['text']=train_data['text'].apply(clean_text) # Strips html, numbers, punctuations, etc.

train_data['text'] = train_data['text'].apply(lambda x: ' '.join([word for word in x.split() if word not in (stop)])) # Stripes stop words

train_data['text']=train_data['text'].apply(preprocessdata) # Lemmatization

# The location and keyword for each tweets are available in some rows

# Concatenate to take those into account

spaces = [' ' for i in range(0, len(train_data.location))]

X = train_data.text + spaces + train_data.location + spaces + train_data.keyword

# word2id

frequent_words = pd.Series(' '.join(X).split()).value_counts()[:vocab_size]

vocabulary = frequent_words.keys().tolist()

def map2vocab_index(text):

word_indices = np.asarray([vocabulary.index(word) for word in text.split() if word in vocabulary]).astype('float32')

return word_indices

X = X.apply(map2vocab_index)

y = np.asarray(train_data.target)

If we look into the length of each input a little bit, we would find this:

length = [len(x) for x in X]

pd.Series(length).describe()

# > output

# count 7613.000000

# mean 11.196769

# std 3.854303

# min 1.000000

# 25% 8.000000

# 50% 11.000000

# 75% 14.000000

# max 27.000000

# dtype: float64

pd.Series(length).quantile(0.9)

# > 16.0 # 90% quantile of the input length

And this is the reason why the above maxlen is chosen – because 90% of the texts have less than 16 words after preprocessing, and we don’t want all the extra zeros when we are doing the padding, which is done by the below code. with train_test_split():

X_train, X_val, y_train, y_val = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.33, random_state=42)

X_train = tf.keras.preprocessing.sequence.pad_sequences(X_train, maxlen=maxlen)

X_val = tf.keras.preprocessing.sequence.pad_sequences(X_val, maxlen=maxlen)

Peeking into the feature validation set, we got what we expected:

X_val[:2]

# > output

# array([[ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

# 8, 40, 261, 159, 159],

# [ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 172, 52,

# 119, 64, 1880, 5586, 119]], dtype=int32)

Now we just need to build, compile and fit the model. The following two classes would be the building blocks of our model:

class TokenAndPositionEmbedding(Layer):

def __init__(self, maxlen, vocab_size, embed_dim):

super(TokenAndPositionEmbedding, self).__init__()

self.token_emb = Embedding(input_dim=vocab_size, output_dim=embed_dim)

self.pos_emb = Embedding(input_dim=maxlen, output_dim=embed_dim)

def call(self, x):

maxlen = tf.shape(x)[-1]

positions = tf.range(start=0, limit=maxlen, delta=1)

positions = self.pos_emb(positions)

x = self.token_emb(x)

return x + positions

class TransformerBlock(Layer):

def __init__(self, embed_dim, num_heads, ff_dim, rate=0.5):

super(TransformerBlock, self).__init__()

self.att = MultiHeadAttention(num_heads=num_heads, key_dim=embed_dim)

self.dropout1 = Dropout(rate)

self.layernorm1 = LayerNormalization(epsilon=1e-6)

self.ffn = Sequential(

[Dense(ff_dim, activation="relu"),

Dense(embed_dim),]

)

self.dropout2 = Dropout(rate)

self.layernorm2 = LayerNormalization(epsilon=1e-6)

def call(self, inputs, training):

attn_output = self.att(inputs, inputs)

attn_output = self.dropout1(attn_output, training=training)

out1 = self.layernorm1(inputs + attn_output)

ffn_output = self.ffn(out1)

ffn_output = self.dropout2(ffn_output, training=training)

return self.layernorm2(out1 + ffn_output)

As you can see they matches the Transformer architecture we discussed in Part 1. If you need a refresher, here is the last article. Now we just need to actually build the model, so we have:

embed_dim = 64 # Embedding size for each token

num_heads = 4 # Number of attention heads

ff_dim = 256 # Hidden layer size in feed forward network inside transformer

def get_model():

inputs = Input(shape=(maxlen,))

embedding_layer = TokenAndPositionEmbedding(maxlen, vocab_size, embed_dim)

x = embedding_layer(inputs)

transformer_block = TransformerBlock(embed_dim, num_heads, ff_dim, rate = 0.1)

x = transformer_block(x)

# transformer_block2 = TransformerBlock(embed_dim, num_heads, ff_dim, rate = 0.1)

# x = transformer_block2(x)

x = GlobalAveragePooling1D()(x)

x = Dropout(0.5)(x)

x = Dense(32, activation="relu")(x)

x = Dropout(0.3)(x)

outputs = Dense(1, activation="sigmoid")(x)

return Model(inputs=inputs, outputs=outputs)

It’s easy to see that for this model, we have several model parameters to tweak around with. The table below are the values I tried corresponding to each of those paramaters.

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| # of transformer blocks | 1, 2, 3, 6 |

| Embedding Dimension | 32, 64, 100, 128, 256, 512 |

| # of attention heads | 2, 4, 8 |

| Hiden Layer Dimension | 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048 |

| Dropout Rate | 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 |

| Learning Rate | 1e-5, 5e-5, 1e-4 |

By experimenting with different combinations and reading other people’s takes and results, I finally chose the values in the code block shown above since it seems to work the best with this problem specifically. I spent the majority of my time tuning the model architecture using these possible parameter values, repeating a few times with each set of value combinations to try verify the results. It’s really fun and after a few times you can see that there is definitely patterns to it. For example, this is hardly a big or medium dataset, and if the model is too complex it can’t even acheive our previous accuracy 75%. Setting Hidden Layer Dimension to be 512 and # of attention heads to 2 usually do the trick and gave us resulting accuracy comparable to our pre-trained model, that is, 75%. Embedding Dimension that is larger than 100 usually make the model worse. More than 2 transformer block also make it worse. Considering that input sequences have at max 16 words, and the dataset is quite small, it’s preferable to have small models to avoid overfitting. At last, a learning rate of 1e-4 is shown to have better performance than 1e-5 or 5e-5 and is therefore chosen.

Below is my code to train the model. The actual code is long and hard to read, so I just showed the most important code here. Full source code is attached in the end. Following the best practices, I used 5-fold Stratified Cross Validation to build 5 different models, and later predict using their average output. It saves the model on each epoch if it’s the best model seen so far based on validation accuracy. It will also stop early if the model stopped improving.

for train_indices, val_indices in StratifiedKFold(5, shuffle=True, random_state=42).split(X_train, y_train):

# ...

model = get_model()

model.compile(optimizer=tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(1e-4),

loss=tf.keras.losses.BinaryCrossentropy(), metrics=["accuracy"])

early_stop = tf.keras.callbacks.EarlyStopping(patience=5)

model_checkpoint = tf.keras.callbacks.ModelCheckpoint(model_checkpoint_path, monitor="val_accuracy", save_best_only=True, save_weights_only=True)

history = model.fit(train_features, train_targets, validation_data=(validation_features, validation_targets), epochs=20, callbacks=[early_stop, model_checkpoint])

Result and Discussion

The final model improved ~75% accuracy to ~78.5% accuracy and boosted my rank up +200. The only thing is that the Transformer in its original form is most suitable for output sequence generation such as Machine Translation, but this is a classification problem. For this kind of problem, it’s better to use a pre-trained variation of the BERT model, of which the objective is to give a good representation of the sequence for downstream application, in our case a classification problem. BERT is pre-trained as a Masked Language Model(50% of the time) and using Next Sentence Prediction(the other 50%). BERT pre-trained models are great for transfering learning use cases like this. In fact, every Kaggle notebook that used the original Transformer model has an accuracy equal or less than 80%, however, every solution on the first page that used BERT has easily at least 82.5% accuracy. It’s not a difficult task to port a BERT model into my solution – I just need to use a tokenizer and then build some Feed Forward Network upon the BERT representation. However, my solution is already pretty long and dense, so I skipped it for now – I’ll use BERT in my next project. I already have an idea of what I want to do. On the other hand, I also want to incorporate some tools to automate experimentation and to version my models and predictions: manual experimentation is chaotic and without documentation, which was a big problem I had in this project.

I learned a lot about fine-tuning through this experience, and have read tutorials, documentations, and implementation codes. It’s been a great learning experience, and now I feel much more comfortable developing ML models using Tensorflow and Keras and has a crude sense of model complexity and performance that needs to be improved upon still. Hope you find something interesting or useful in this article as well.

Source Code

References

- Transformers For Text Classification: https://blog.paperspace.com/transformers-text-classification

- Kaggle, Transformer Encoder for Classification in Pytorch: https://www.kaggle.com/code/zhuyuqiang/transformer-encoder-for-classification-in-pytorch

- Kaggle, Disaster Tweets Classification: Transformer: https://www.kaggle.com/code/lonnieqin/disaster-tweets-classification-transformer